Which migraine medications are most helpful?

If you suffer from the throbbing, intense pain set off by migraine headaches, you may well wonder which medicines are most likely to offer relief. A recent study suggests a class of drugs called triptans are the most helpful option, with one particular drug rising to the top.

The study drew on real-world data gleaned from more than three million entries on My Migraine Buddy, a free smartphone app. The app lets users track their migraine attacks and rate the helpfulness of any medications they take.

Dr. Elizabeth Loder, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and chief of the Division of Headache at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, helped break down what the researchers looked at and learned that could benefit anyone with migraines.

What did the migraine study look at?

Published in the journal Neurology, the study included self-reported data from about 278,000 people (mostly women) over a six-year period that ended in July 2020. Using the app, participants rated migraine treatments they used as “helpful,” “somewhat helpful,” or “unhelpful.”

The researchers looked at 25 medications from seven drug classes to see which were most helpful for easing migraines. After triptans, the next most helpful drug classes were ergots such as dihydroergotamine (Migranal, Trudhesa) and anti-emetics such as promethazine (Phenergan). The latter help ease nausea, another common migraine symptom.

“I’m always happy to see studies conducted in a real-world setting, and this one is very clever,” says Dr. Loder. The results validate current guideline recommendations for treating migraines, which rank triptans as a first-line choice. “If you had asked me to sit down and make a list of the most helpful migraine medications, it would be very similar to what this study found,” she says.

What else did the study show about migraine pain relievers?

Ibuprofen, an over-the-counter pain reliever sold as Advil and Motrin, was the most frequently used medication in the study. But participants rated it “helpful” only 42% of the time. Only acetaminophen (Tylenol) was less helpful, helping just 37% of the time. A common combination medication containing aspirin, acetaminophen, and caffeine (sold under the brand name Excedrin) worked only slightly better than ibuprofen, or about half the time.

When researchers compared helpfulness of other drugs to ibuprofen, they found:

- Triptans scored five to six times more helpful than ibuprofen. The highest ranked drug, eletriptan, helped 78% of the time. Other triptans, including zolmitriptan (Zomig) and sumatriptan (Imitrex), were helpful 74% and 72% of the time, respectively. In practice, notes Dr. Loder, eletriptan seems to be just a tad better than the other triptans.

- Ergots were rated as three times more helpful than ibuprofen.

- Anti-emetics were 2.5 times as helpful as ibuprofen.

Do people take more than one medicine to ease migraine symptoms?

In this study, two-thirds of migraine attacks were treated with just one drug. About a quarter of the study participants used two drugs, and a smaller number used three or more drugs.

However, researchers weren’t able to tease out the sequence of when people took the drugs. And with anti-nausea drugs, it’s not clear if people were rating their helpfulness on nausea rather than headache, Dr. Loder points out. But it’s a good reminder that for many people who have migraines, nausea and vomiting are a big problem. When that’s the case, different drug formulations can help.

Are pills the only option for migraine relief?

No. For the headache, people can use a nasal spray or injectable version of a triptan rather than pills. Pre-filled syringes, which are injected into the thigh, stomach, or upper arm, are underused among people who have very rapid-onset migraines, says Dr. Loder. “For these people, injectable triptans are a game changer because pills don’t work as fast and might not stay down,” she says.

For nausea, the anti-emetic ondansetron (Zofran) is very effective, but one of the side effects is headache. You’re better off using promethazine or prochlorperazine (Compazine), both of which treat nausea but also help ease headache pain, says Dr. Loder.

Additionally, many anti-nausea drugs are available as rectal suppositories. This is especially helpful for people who have “crash” migraines, which often cause people to wake up vomiting with a migraine, she adds.

What are the limitations of this migraine study?

The data didn’t include information about the timing, sequence, formulation, or dosage of the medications. It also omitted two classes of newer migraine medications — known as gepants and ditans — because there was only limited data on them at the time of the study. These options include

- atogepant (Qulipta) and rimegepant (Nurtec)

- lasmiditan (Reyvow).

“But based on my clinical experience, I don’t think that any of these drugs would do a lot better than the triptans,” says Dr. Loder.

Another shortcoming is the study population: a selected group of people who are able and motivated to use a migraine smartphone app. That suggests their headaches are probably worse than the average person, but that’s exactly the population for whom this information is needed, says Dr. Loder.

“Migraines are most common in young, healthy people who are trying to work and raise children,” she says. It’s good to know that people using this app rate triptans highly, because from a medical point of view, these drugs are well tolerated and have few side effects, she adds.

Are there other helpful takeaways?

Yes. In the study, nearly half the participants said their pain wasn’t adequately treated. A third reported using more than one medicine to manage their migraines.

If you experience these problems, consult a health care provider who can help you find a more effective therapy. “If you’re using over-the-counter drugs, consider trying a prescription triptan,” Dr. Loder says. If nausea and vomiting are a problem for you, be sure to have an anti-nausea drug on hand.

She also recommends using the Migraine Buddy app or the Canadian Migraine Tracker app (both are free), which many of her patients find helpful for tracking their headaches and triggers.

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

Julie Corliss is the executive editor of the Harvard Heart Letter. Before working at Harvard, she was a medical writer and editor at HealthNews, a consumer newsletter affiliated with The New England Journal of Medicine. She … See Full Bio View all posts by Julie Corliss

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Howard LeWine is a practicing internist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Chief Medical Editor at Harvard Health Publishing, and editor in chief of Harvard Men’s Health Watch. See Full Bio View all posts by Howard E. LeWine, MD

What is a tongue-tie? What parents need to know

The tongue is secured to the front of the mouth partly by a band of tissue called the lingual frenulum. If the frenulum is short, it can restrict the movement of the tongue. This is commonly called a tongue-tie.

Children with a tongue-tie can’t stick their tongue out past their lower lip, or touch their tongue to the top of their upper teeth when their mouth is open. When they stick out their tongue, it looks notched or heart-shaped. Since babies don’t routinely stick out their tongues, a baby’s tongue may be tied if you can’t get a finger underneath the tongue.

How common are tongue-ties?

Tongue-ties are common. It’s hard to say exactly how common, as people define this condition differently. About 8% of babies under age one may have at least a mild tongue-tie.

Is it a problem if the tongue is tied?

This is really important: tongue-ties are not necessarily a problem. Many babies, children, and adults have tongue-ties that cause them no difficulties whatsoever.

There are two main ways that tongue-ties can cause problems:

- They can cause problems with breastfeeding by making it hard for some babies to latch on well to the mother’s nipple. This causes difficulty with feeding for the baby and sore nipples for the mother. It doesn’t happen to all babies with a tongue-tie; many of them can breastfeed successfully. Tongue-ties are not to blame for gassiness or fussiness in a breastfed baby who is gaining weight well. Babies with tongue-ties do not have problems with bottle-feeding.

- They can cause problems with speech. Some children with tongue-ties may have difficulty pronouncing certain sounds, such as t, d, z, s, th, n, and l. Tongue-ties do not cause speech delay.

What should you do if think your baby or child has a tongue-tie?

If you think that your newborn is not latching well because of a tongue-tie, talk to your doctor. There are many, many reasons why a baby might not latch onto the breast well. Your doctor should take a careful history of what has been going on, and do a careful examination of your baby to better understand the situation.

You should also have a visit with a lactation specialist to get help with breastfeeding — both because there are lots of reasons why babies have trouble with latching on, and also because many babies with a tongue-tie can nurse successfully with the right techniques and support.

Talk to your doctor if you think that a tongue-tie could be causing problems with how your child pronounces words. Many children just take some time to learn to pronounce certain sounds. It is also a good idea to have an evaluation by a speech therapist before concluding that a tongue-tie is the problem.

What can be done about a tongue-tie?

When necessary, a doctor can release a tongue-tie using a procedure called a frenotomy. A frenotomy can be done by simply snipping the frenulum, or it can be done with a laser.

However, nothing should be done about a tongue-tie that isn’t causing problems. While a frenotomy is a relatively minor procedure, complications such as bleeding, infection, or feeding difficulty sometimes occur. So it’s never a good idea to do it just to prevent problems in the future. The procedure should only be considered if the tongue-tie is clearly causing trouble.

It’s also important to know that clipping a tongue-tie doesn’t always solve the problem, especially with breastfeeding. Studies do not show a clear benefit for all babies or mothers. That’s why it’s important to work with a lactation expert before even considering a frenotomy.

If a newborn with a tongue-tie isn’t latching well despite strong support from a lactation expert, then a frenotomy should be considered, especially if the baby is not gaining weight. If it is done, it should be done early on and by someone with training and experience in the procedure.

What else should parents know about tongue-tie procedures?

Despite the fact that the evidence for the benefits of frenotomy is murky, many providers are quick to recommend them. If one is being recommended for your child, ask questions:

- Make sure you know exactly why it is being recommended.

- Ask whether there are any other options, including waiting.

- Talk to other health care providers on your child’s care team, or get a second opinion.

About the Author

Claire McCarthy, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing

Claire McCarthy, MD, is a primary care pediatrician at Boston Children’s Hospital, and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School. In addition to being a senior faculty editor for Harvard Health Publishing, Dr. McCarthy … See Full Bio View all posts by Claire McCarthy, MD

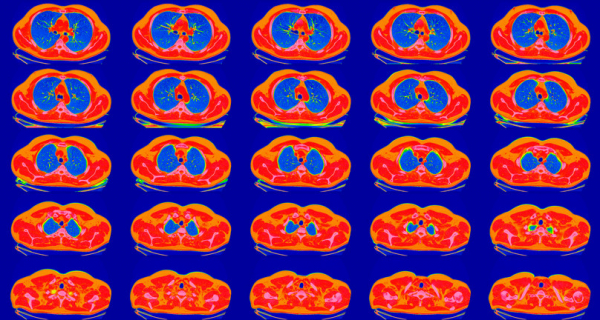

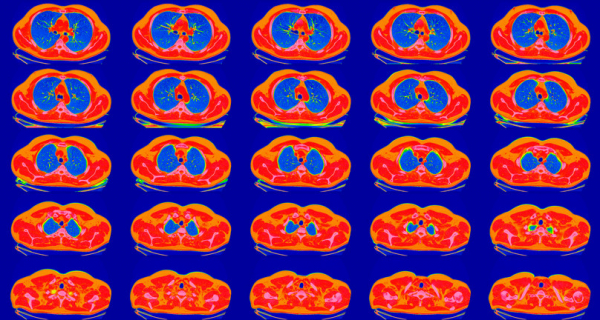

New guidelines aim to screen millions more for lung cancer

Lung cancer kills more Americans than any other malignancy. The latest American Cancer Society (ACS) updated guidelines aim to reduce deaths by considerably expanding the pool of people who seek annual, low-dose CT lung screening scans.

Advocates hope the new advice will prompt more people at risk for lung cancer to schedule yearly screening, says Dr. Carey Thomson, director of the Multidisciplinary Thoracic Oncology and Lung Cancer Screening Program at Harvard-affiliated Mount Auburn Hospital, and chair of the Early Detection Task Group for the ACS/National Lung Cancer Roundtable. Currently, fewer than one in 10 eligible people in the US follow through on recommended lung screenings.

What are the major changes in the new ACS lung cancer guidelines?

The updated ACS guidelines are aimed at high-risk individuals, all of whom have a smoking history. And unlike previous ACS recommendations, it doesn’t matter how long ago a person quit smoking. The updated guidelines also lower the bar on amount of smoking and widen the age window to seek screening, which aligns with 2021 recommendations issued by the US Preventive Services Task Force.

These changes combined may mean another six to eight million people will be eligible to have screening.

How many people get lung cancer?

Although lung cancer is the third most common malignancy in the United States, it’s the deadliest, killing more people than colorectal, breast, prostate, and cervical cancers combined. In 2023, about 238,000 Americans will be diagnosed with lung cancer and 127,000 will die of it, according to ACS estimates.

What is the major risk factor for lung cancer?

While people who have never smoked can get lung cancer, smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke is a major risk factor for this illness. Smoking is linked to as many as 80% to 90% of lung cancer deaths, according to the CDC.

Indeed, people who smoke are 15 to 30 times more likely to develop or die from lung cancer than those who don’t. The longer someone smokes and the more cigarettes they smoke each day, the higher their risks.

Is lung cancer easier to treat if found in early stages?

Yes. As with many cancers, detecting lung malignancies in their earliest stages is pivotal to improving survival.

Depending on the type of lung cancer diagnosed, up to 80% to 90% of people with a single, early-stage tumor that can be removed surgically can survive five years or longer, says the American Society of Clinical Oncology. The number of people who survive long-term becomes smaller as tumors grow larger, and if they spread to lymph nodes or other areas of the body.

Should you consider lung CT screening?

The updated ACS guidelines recommend screening if you:

- Are 50 to 80 years old. This age range is expanded from the prior ACS recommended cutoff of 55 to 74.

- Are a current or previous smoker. This includes anyone who smoked, not just smokers who quit within the past 15 years.

- Smoked 20 or more pack-years. This means smoking an average of 20 cigarettes per day for 20 years or 40 cigarettes per day for 10 years. Previously, the eligibility cutoff was 30 or more pack-years.

“While an expansion in the number of people screened for lung cancer will find additional early tumors, it also means more false positives will be detected,” says Howard LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor at Harvard Health Publishing. False positives are worrisome spots on a CT scan that are not cancer. But they usually require additional testing, perhaps a biopsy and even surgery for something that was harmless.

Before scheduling a low-dose CT lung screening, you’ll need to talk to a health professional about the screening process, your risks, whether it will be covered by your health insurance. Previously, an in-person medical appointment was required.

Why did the ACS change the years-since-quitting screening requirement?

Much international research suggests that the number of years since someone stopped smoking has little or no bearing on their risk of developing lung cancer, says Dr. Thomson.

“You have an equal likelihood of developing lung cancer whether you quit more than 15 years ago or more recently,” she says. “The recommendations on the national scene say that we need to be screening more people and make it easier to be screened. One of the ways to do that is to drop the quit history requirement.”

If you’re eligible for screening, how often should you have it?

Every year, says the ACS.

But why not screen for lung cancer for several years and then take a break, as is done with a malignancy such as cervical cancer? Research hasn’t been done to demonstrate that this type of approach is safe, Dr. Thomson says.

“We know that a large percentage of lung cancers identified in people through low-dose CT scans are identified after their first year of screening,” she says. “And some forms of lung cancer can move quickly, which is part of the reason it’s as deadly as it is.”

Did all guidelines organizations drop the years-since-quitting requirement?

No. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force — which, along with the ACS and other groups, recommend national standards for screenings — haven’t yet signed on to the ACS approach. These two groups maintain that only smokers who quit 15 or fewer years ago should remain eligible for screening.

However, guidelines issued by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network mesh with the new ACS recommendations by not having a years-since-quitting threshold.

Because Medicare and other health insurers may have slightly different rules to determine payment for lung cancer CT screening, it’s best to confirm this with your health care provider or insurer before getting tested.

About the Author

Maureen Salamon, Executive Editor, Harvard Women's Health Watch

Maureen Salamon is executive editor of Harvard Women’s Health Watch. She began her career as a newspaper reporter and later covered health and medicine for a wide variety of websites, magazines, and hospitals. Her work has … See Full Bio View all posts by Maureen Salamon

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Howard LeWine is a practicing internist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Chief Medical Editor at Harvard Health Publishing, and editor in chief of Harvard Men’s Health Watch. See Full Bio View all posts by Howard E. LeWine, MD

Discrimination at work is linked to high blood pressure

Experiencing discrimination in the workplace — where many adults spend one-third of their time, on average — may be harmful to your heart health.

A 2023 study in the Journal of the American Heart Association found that people who reported high levels of discrimination on the job were more likely to develop high blood pressure than those who reported low levels of workplace discrimination.

Workplace discrimination refers to unfair conditions or unpleasant treatment because of personal characteristics — particularly race, sex, or age.

How can discrimination affect our health?

“The daily hassles and indignities people experience from discrimination are a specific type of stress that is not always included in traditional measures of stress and adversity,” says sociologist David R. Williams, professor of public health at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Yet multiple studies have documented that experiencing discrimination increases risk for developing a broad range of factors linked to heart disease. Along with high blood pressure, this can also include chronic low-grade inflammation, obesity, and type 2 diabetes.

More than 25 years ago, Williams created the Everyday Discrimination Scale. This is the most widely used measure of discrimination’s effects on health.

Who participated in the study of workplace discrimination?

The study followed a nationwide sample of 1,246 adults across a broad range of occupations and education levels, with roughly equal numbers of men and women.

Most were middle-aged, white, and married. They were mostly nonsmokers, drank low to moderate amounts of alcohol, and did moderate to high levels of exercise. None had high blood pressure at the baseline measurements.

How was discrimination measured and what did the study find?

The study is the first to show that discrimination in the workplace can raise blood pressure.

To measure discrimination levels, researchers used a test that included these six questions:

- How often do you think you are unfairly given tasks that no one else wanted to do?

- How often are you watched more closely than other workers?

- How often does your supervisor or boss use ethnic, racial, or sexual slurs or jokes?

- How often do your coworkers use ethnic, racial, or sexual slurs or jokes?

- How often do you feel that you are ignored or not taken seriously by your boss?

- How often has a coworker with less experience and qualifications gotten promoted before you?

Based on the responses, researchers calculated discrimination scores and divided participants into groups with low, intermediate, and high scores.

- After a follow-up of roughly eight years, about 26% of all participants reported developing high blood pressure.

- Compared to people who scored low on workplace discrimination at the start of the study, those with intermediate or high scores were 22% and 54% more likely, respectively, to report high blood pressure during the follow-up.

How could discrimination affect blood pressure?

Discrimination can cause emotional stress, which activates the body’s fight-or-flight response. The resulting surge of hormones makes the heart beat faster and blood vessels narrow, which causes blood pressure to rise temporarily. But if the stress response is triggered repeatedly, blood pressure may remain consistently high.

Discrimination may arise from unfair treatment based on a range of factors, including race, gender, religious affiliation, or sexual orientation. The specific attribution doesn’t seem to matter, says Williams. “Broadly speaking, the effects of discrimination on health are similar, regardless of the attribution,” he says, noting that the Everyday Discrimination Scale was specifically designed to capture a range of different forms of discrimination.

What are the limitations of this study?

One limitation of this recent study is that only 6% of the participants were nonwhite, and these individuals were less likely to take part in the follow-up session of the study. As a result, the study may not have fully or accurately captured workplace discrimination among people from different racial groups. In addition, blood pressure was self-reported, which may be less reliable than measurements directly documented by medical professionals.

What may limit the health impact of workplace discrimination?

At the organizational level, no studies have directly addressed this issue. Preliminary evidence suggests that improving working conditions, such as decreasing job demands and increasing job control, may help lower blood pressure, according to the study authors. In addition, the American Heart Association recently released a report, Driving Health Equity in the Workplace, that aims to address drivers of health inequities in the workplace.

Encouraging greater awareness of implicit bias may be one way to help reduce discrimination in the workplace. Implicit bias refers to the unconscious assumptions and prejudgments people have about groups of people that may underlie some discriminatory behaviors. You can explore implicit biases with these tests, which were developed at Harvard and other universities.

On an individual level, stress management training can reduce blood pressure. A range of stress-relieving strategies may offer similar benefits. Regularly practicing relaxation techniques or brief mindfulness reflections, learning ways to cope with negative thoughts, and getting sufficient exercise can help.

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

Julie Corliss is the executive editor of the Harvard Heart Letter. Before working at Harvard, she was a medical writer and editor at HealthNews, a consumer newsletter affiliated with The New England Journal of Medicine. She … See Full Bio View all posts by Julie Corliss

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Howard LeWine is a practicing internist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Chief Medical Editor at Harvard Health Publishing, and editor in chief of Harvard Men’s Health Watch. See Full Bio View all posts by Howard E. LeWine, MD

New research shows little risk of infection from prostate biopsies

Infections after a prostate biopsy are rare, but they do occur. Now research shows that fewer than 2% of men develop confirmed infections after prostate biopsy, regardless of the technique used.

In the United States, doctors usually thread a biopsy needle through the rectum and then into the prostate gland while watching their progress on an ultrasound machine. This is called a transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy (TRUS). Since the biopsy needle passes through the rectum, there's a chance that fecal bacteria will be introduced into the prostate or escape into the bloodstream. For that reason, doctors typically treat a patient with antibiotics before initiating the procedure.

Alternatively, the biopsy needle can be passed through the peritoneum, which is a patch of skin between the anus and the base of the scrotum. These transperitoneal prostate (TP) biopsies, as they are called, are also performed with ultrasound guidance, and since they bypass the rectum, antibiotics typically aren't required. In that way, TP biopsies help to keep antibiotic resistance at bay, and European medical guidelines strongly favor this approach, citing a lower risk of infection.

Study goals and methodology

TP biopsies aren't widely adopted in the United States, in part because doctors lack familiarity with the method and need further training to perform it. The technology is steadily improving, and TP biopsies are increasingly being conducted in office settings around the country. But questions remain about how TRUS and TP biopsies compare in terms of their infectious complications.

To investigate, researchers at Albany Medical Center in New York conducted the first-ever randomized clinical trial comparing infection risks associated with either method. The results were published in February in the Journal of Urology.

The Albany team randomized 718 men to either a TRUS or TP biopsy. Nearly all the men who got a TRUS biopsy (and with few exceptions, none of the TP-treated men) first received a single-day course of antibiotics. All the biopsies were administered between 2019 and 2022 by three urologists working at the Medical Center's affiliated and nonaffiliated hospitals.

The men were then monitored for fever, genitourinary infections, antibiotic prescriptions for suspected or confirmed infections, sepsis, and infection-related contacts with caregivers. Researchers collected data during a visit conducted two weeks after a biopsy procedure, and then by phone over an additional 30-day period following this initial meeting.

What the researchers found

According to the results, 1.1% of men in the TRUS group and 1.4% of men in the transperineal group wound up with confirmed infections. The difference was not statistically significant. If "possible" infections were counted (for example, antibiotic prescriptions for fever), then the rates increased to 2.6% and 2.7% of men in the TRUS and TP groups, respectively.

Fever was the most frequent complication, reported by six participants in each group. One participant from each group also developed noninfectious urinary retention, requiring the temporary use of a catheter. None of the men developed sepsis or required post-biopsy treatments for bleeding.

The study had some limitations: Nearly all the participants were white, and so the results may not be applicable to men from other racial and ethnic groups. Furthermore, since all the men were biopsied by a single institution, it's unclear if the findings are generalizable in other settings. Still, the study provides reassuring evidence that both types of biopsies "appear safe and viable options for clinical practice," the authors concluded.

Commentary from experts

"The paper provides needed evidence that TP biopsies without antibiotics are about as safe and efficacious as TRUS biopsies with antibiotics," said Dr. Marc Garnick, the Gorman Brothers Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. The findings also help to dispel a growing view that transperineal biopsies are superior, Dr. Garnick pointed out.

"Recent years have witnessed a marked interest and surge in the transperineal approach, primarily driven by early studies suggesting a lower risk of infectious complications compared with transrectal biopsy," said Dr. Boris Gershman, a urologist at Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, and a member of Harvard Health Publishing's Annual Report on Prostate Diseases advisory board.

"Interestingly, the investigators find no difference in infectious complications, and it will be important to see if other ongoing studies report similar results," Dr. Gershman continued. "In addition to safety, we also need to confirm whether there are any meaningful differences between the two approaches with respect to cancer detection rates."

About the Author

Charlie Schmidt, Editor, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases

Charlie Schmidt is an award-winning freelance science writer based in Portland, Maine. In addition to writing for Harvard Health Publishing, Charlie has written for Science magazine, the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Environmental Health Perspectives, … See Full Bio View all posts by Charlie Schmidt

About the Reviewer

Marc B. Garnick, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Marc B. Garnick is an internationally renowned expert in medical oncology and urologic cancer. A clinical professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, he also maintains an active clinical practice at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical … See Full Bio View all posts by Marc B. Garnick, MD